By Wahome Ngatia

In the dusty expanses of a sub-county in Western Kenya, Mama Atieno is a minor celebrity. A dedicated Community Health Promoter (CHP), her small wooden chest is filled not with medicine or diagnostic kits, but with certificates. She has ten of them—glossy, embossed, and signed by ten different international NGOs. Each represents a week spent in a hotel “capacity-building” seminar on malaria, maternal health, or sanitation.

Mama Atieno has been “empowered” more times than she can count. She has received thousands of shillings in “sitting allowances” and per diems. Yet, as she walks the three miles to visit a sick child, she does so without a bicycle, without a functional smartphone for reporting, and without the basic commodities needed to save a life. She is a victim of what I call “The Silo Syndrome”—a fragmented, uncoordinated humanitarian landscape that prioritizes donor checklists over community impact.

For years, this has been the unspoken reality of Kenya’s development sector. NGOs arrive in counties like gale-force winds, blowing in with well-funded, short-term interventions that overlap, duplicate, and ultimately dissipate without leaving a trace of institutional memory. It is a problem that has finally caught the attention of the highest levels of government.

The Kagwe Reality Check: Loans, Not Free Money

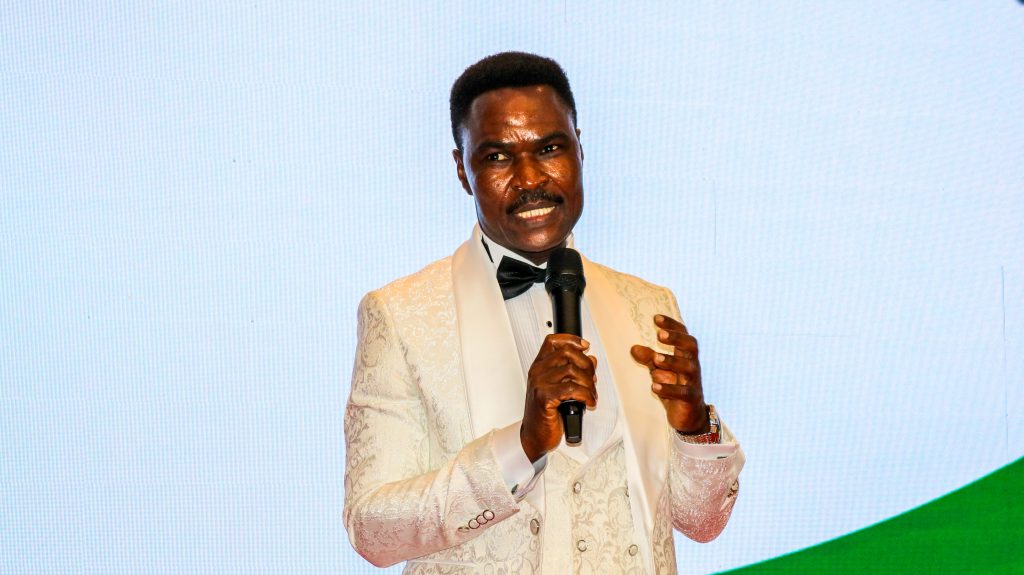

Last week, Agriculture Cabinet Secretary Mutahi Kagwe pulled the rug out from under the “donor” euphemism. Speaking at a Joint National Project Steering Committee meeting, Kagwe delivered a masterclass in public administration realism. “The word ‘donor’ is deceiving,” he remarked, his voice echoing through the boardroom. “In the English language, it sounds like free money. But these are loans. These are facilities we have to pay back.”

Kagwe’s frustration was palpable—and justified. He cited instances where donor-funded projects under his ministry were riddled with “loose arrangements,” operating in silos without a comprehensive alignment with national policy. Most damningly, he pointed to procurement lists that looked more like an import catalog for Polish industries than a plan for Kenyan self-reliance. “We cannot be buying ice cream makers and motorbikes from Poland when these are things we make here,” he noted.

His message was clear: The era of the “parallel government” is over. Whether it is agriculture or health, every non-state actor must now sit at the table of the state’s comprehensive agenda.

The Diagnosis: The Per Diem Economy and the Overlap Crisis

The problem Kagwe diagnosed in agriculture is even more acute in the humanitarian and health sectors. In the NGO world, “coordination” is often a buzzword used in grant applications but ignored in the field.

Kenya already has many of the ingredients needed to fix this problem. What is missing is a deliberate, professional coordination architecture.

When three different NGOs descend on a single county to train the same 50 health promoters on nearly identical topics, they aren’t just wasting money—they are distorting the local economy. We have created a “shadow economy of allowances” where government officials and community workers are incentivized to attend meetings rather than deliver services. A recent Auditor General report flagged Sh2.5 billion in unaccounted donor funds, much of it swallowed by “unsupported domestic travel and subsistence.”

This overlap creates “intervention fatigue.” Communities are surveyed to death, “capacitated” into exhaustion, but rarely supported into sustainability. When the NGO’s three-year cycle ends, they pack their Land Cruisers and leave, leaving behind a government that was never truly involved and a community that has learned to wait for the next per diem rather than build local systems.

Global Lessons: The Rwandan and Ethiopian Models

Kenya does not need to reinvent the wheel. We only need to look at our neighbors who have mastered the art of “Aid Effectiveness.”

Take Rwanda. Under its Imihigo system, every development partner—including NGOs—must align their work plans with the government’s District Development Strategies. They don’t just “operate” in a district; they sign a performance contract. Rwanda utilizes a “Single Project Implementation Unit” (SPIU) model within its ministries. This ensures that whether a project is funded by the World Bank, USAID, or a private foundation, it is managed through a centralized government unit that prevents duplication and ensures procurement supports local industries.

Similarly, Ethiopia’s NGO law (though controversial in its early versions) was born out of a desire to ensure that at least 70% of NGO funding goes directly to service delivery, with only 30% for administration. This “70/30 Rule” forced a shift from hotel-based workshops to actual investments in clinics and irrigation.

The Strategist’s Prescription: A New Architecture for Coordination

If I were advising the National Treasury and the Council of Governors today, my proposal would be built on three pillars of “Collaborative Sovereignty”:

1. The National NGO Activity Map (The Digital Registry)

The government must move beyond mere “registration” with the NGO Coordination Board. We need a real-time, mandatory digital dashboard where every NGO must map its activities down to the sub-county level. If an NGO wants to train CHPs in Busia, the system should immediately flag that three other organizations are already doing so. This would force NGOs to either collaborate or move their resources to underserved areas like Turkana or Marsabit.

2. Performance-Based Incentives, Not Sitting Allowances

We must kill the per diem culture before it kills our work ethic. Following the blueprint of the KEMRI and Living Goods study in Busia, we should transition to performance-based financing. Instead of paying Mama Atieno to sit in a room, we should pay her based on the number of children she immunizes or the malaria cases she treats. This shifts the focus from “inputs” (meetings) to “outcomes” (health).

3. Procurement Sovereignty

As CS Kagwe rightly pointed out, donor-funded projects must be “citizen-driven.” We should implement a “Buy Kenya, Build Kenya” mandate for all donor-funded procurement. If a project needs motorbikes, they must be sourced from local assembly plants. This ensures that even “loans” stimulate our local economy and create jobs for the same youth the NGOs claim to be helping.

Moving Toward a Unified Front

The goal is not to chase away NGOs or stifle the goodwill of development partners. Rather, it is to invite them into a more mature, respectful partnership. We need their innovation, their speed, and their capital—but we need it on our terms, aligned with our Vision 2030 goals.

Policy makers must realize that coordination is not an administrative burden; it is a strategic imperative. When we align, we don’t just save money; we amplify impact. We move from a collection of scattered “projects” to a unified “system.”

Mama Atieno doesn’t need an eleventh certificate. She needs a bicycle, a kit of essential medicines, and a government that knows exactly who she is and what she needs to succeed. By heeding the candid warnings of leaders like Mutahi Kagwe and adopting a more disciplined, state-led coordination framework, we can ensure that every shilling—whether a loan or a grant—actually changes a life.

It is time to stop the overlap and start the impact.

The name has been changed to protect privacy.