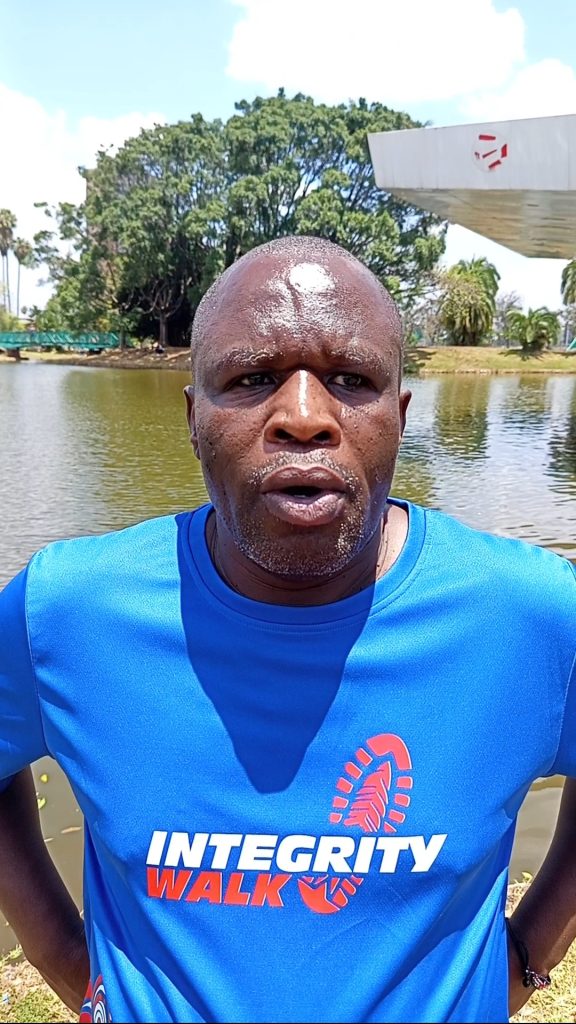

By Wahome Ngatia

Nutrition International (NI) has emerged as a standout development partner in Kenya for one reason: it trusts counties with money — but only under strict accountability controls. This bold, tightly-managed approach has earned NI the “Best in Government Partnership NGO” award and reinforced its reputation as one of the most disciplined nutrition actors in the country.

At NI’s Nairobi offices, Country Manager Martha Nyagaya explained that their model rests on a simple idea rarely practiced in international development: treat every county as unique, and make them co-invest in their own solutions.

“We give money to counties directly and ensure that they pass a measure of accountability so that we can give them the money,” she told this writer.

Direct funding — with strict accountability

When NI signs a partnership with a county, that county must agree to open a special-purpose account, channel the funds into its County Revenue Fund and record all transactions through the Integrated Financial Management Information System (IFMIS).

This ensures the Auditor General can follow every shilling. Counties that hesitate simply don’t get funded.

NI also does not offer grants. It matches county investments on a 1:1 basis. If County A commits KSh 34 million to a nutrition upgrade, NI matches the same amount. Counties must put skin in the game.

The organisation operates on a five-year cycle funded entirely by the Canadian government. For the latest cycle, NI received CAD 316 million (KSh 29.20 billion), making it one of the most stable and predictable nutrition funders in the region.

This has enabled NI to support counties such as Vihiga, Makueni, Samburu, Kiambu and others — but only where accountability is airtight.

Adaptive solutions — not one-size-fits-all

NI’s value is not only in funding but in the customisation of interventions.

In Samburu, where recurring drought pushes families to the edge of survival, NI-supported maternal nutrition programmes have strengthened the outreach of community health volunteers. Local officers say babies who once hovered dangerously close to severe acute malnutrition now have a stronger chance of recovery.

In Makueni, NI’s work aligns with the county’s strong food systems. Green grams, sorghum and pigeon peas — staples of the semi-arid region — are being explored as anchors in a proposed school meal policy, linking nutrition to local agriculture.

In Kiambu, where overweight and obesity among children is rising, NI has encouraged dietary education and micronutrient interventions that recognise this rarely-discussed “second side” of Kenya’s malnutrition problem.

This county-specific approach has earned NI several recognitions: a Beyond Zero award by former First Lady Margaret Kenyatta, an honour from the Ministry of Health, and awards from Nandi and Elgeyo Marakwet counties.

A country facing the triple burden

The need could not be clearer. Kenya’s latest national data shows that 18% of children under five remain stunted.

Over one million children nationally are affected by stunting or chronic undernutrition — a number that still carries long-term consequences for learning, immunity and lifetime income.

According to WHO, Kenya is among nations battling the triple burden of malnutrition:

- undernutrition,

- micronutrient deficiencies, and

- rising overweight/obesity.

UNICEF has warned that Kenya could have nearly one million obese children by 2030 if dietary trends don’t change.

Nyagaya says this complexity is why NI refuses to fund generic, copy-paste interventions.

“Kenya is one of the countries in the world that suffers all forms of malnourishment. In the North East you may find children who are severely undernourished, while in Central Kenya you find kids who are overweight due to what they consume,” she explained.

Building nutrition policy from the ground up

Alongside its county partnerships, NI is working with the Ministry of Education to design a minimum acceptable school meal programme. The proposal uses county-specific food varieties to create affordable, balanced meals for schoolchildren.

The organisation is also distinct in how it operates. NI keeps its administrative costs low: no branded vehicles, no heavy visibility campaigns and no lavish field operations.

“We are required to approach our interventions with humility. That’s why you won’t see our logos on different things. Going public about our impact is not a necessity nor a focus,” Nyagaya said.

Their mission is clear: eliminate malnutrition in all its forms — quietly, locally and effectively.

A quiet but powerful model for development

Malnutrition remains one of Kenya’s most persistent inequalities — from underfed infants in Samburu to overweight schoolchildren in Kiambu. NI’s county-matching model offers a compelling lesson for development partners: trust local governments, demand transparency, and design solutions from the ground up.

If Kenya is to break its generational cycle of nutrition inequality, development must look more like NI’s model — lean, accountable, and anchored in the priorities of the counties themselves. It is a blueprint not only for Kenya, but for how development should work across Africa.