By Wahome Ngatia

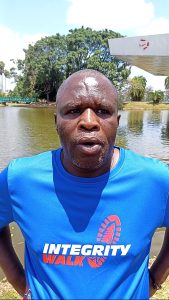

In an interview, Larry Blackstock, an employee in an INGO, told NGOs Hub that Kenyan employees are paid significantly lower than their international counterparts. It is a reality he has lived with for nearly 25 years in the humanitarian world — a sector built on the rhetoric of justice and equality, but one that often mirrors the very inequalities it claims to fight.

Blackstock, who has served in multiple conflict and refugee operations across Africa, says the disparity is stark. “The biggest cost is remuneration,” he explained. “About 75 percent of that amount covers international staff salaries, while 25 percent goes to the local workforce. The irony is that nationals are significantly more in number.”

His experience speaks to a long-standing truth in the aid industry: while local staff shoulder most of the work and understand the context best, it is expatriates who dominate the payroll.

Across Africa, the pattern is similar. Local development professionals in Nigeria, Ethiopia and Uganda have repeatedly challenged salary scales that pay them a fraction — sometimes as little as one-tenth — of what their foreign colleagues earn. Larry’s concerns echo a wider reckoning in the sector about racialised power structures and internal inequalities.

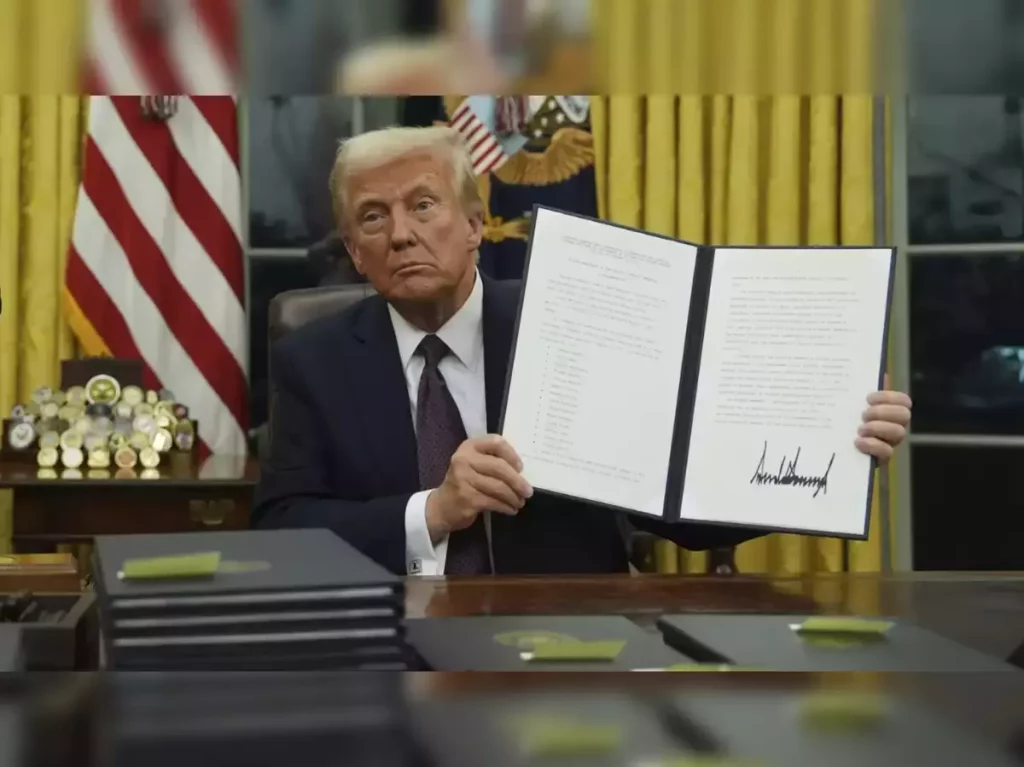

It is into this ongoing debate that Oxfam yesterday released its latest report, Kenya’s Inequality Crisis: The Great Economic Divide. And if Larry’s testimony reveals inequality inside the NGO sector, Oxfam’s data shows the same story playing out across an entire nation.

A Nation Growing — But for Whom?

The report lands at a moment when many Kenyans are increasingly vocal about the cost of living, taxation and public services that have failed to keep pace with their needs. According to Oxfam, Kenya’s economic model has expanded national wealth while shrinking opportunities for ordinary citizens.

The numbers are sobering. The richest 125 Kenyans now hold more wealth than 42.6 million people — roughly 77 percent of the entire population. Poverty has also deepened: seven million more Kenyans have fallen into extreme poverty since 2015. This is happening despite a decade of steady economic growth, averaging 5 percent per year. It is growth that looks good on paper but feels hollow in real life.

In many ways, the inequality playing out in Kenya’s public sphere is not unlike the NGO industry’s internal hierarchy. A small group enjoys the benefits. The majority carry the weight.

Inside Oxfam: Who They Are and Why Their Voice Matters

Oxfam International, founded more than 80 years ago, is among the world’s most influential humanitarian and development networks. Known for its authoritative inequality reports that shape policy discussions at Davos, the UN and finance ministries across continents, Oxfam has become a global reference point on how wealth is created — and who it leaves behind.

Their newest Kenya-focused report is one of their most comprehensive national analyses in recent years, bringing together data on wealth, taxation, social services, gender disparities and labour markets.

And its findings are unsettling.

Education: When a Child’s Future Depends on Their Parents’ Income

Oxfam paints a picture of an education system deeply shaped by inequality.

As per the report, children from the wealthiest households enjoy nearly five more years of schooling than those from the poorest families. Their research showed that more than 1.1 million primary school-age children are out of school.

Government spending per pupil has dropped dramatically — now worth just 18 percent of what it was in 2003 when adjusted for inflation.

While elite private schools thrive, public schools — especially in rural areas and informal settlements — struggle with teacher shortages, inadequate infrastructure and inconsistent funding. The opportunities a child receives are often decided long before they enter a classroom.

Across Africa, the pattern is similar. In South Africa, Uganda and Tanzania, poorer families face the steepest barriers: school fees, transport costs, and the labour burden placed on girls. Inequality in education becomes inequality in adulthood.

Health: A System Where Wealth Determines Who Gets Treated First

The healthcare story is equally alarming. Oxfam highlights chronic underfunding, fractured reforms and a growing reliance on private providers.

They said that only 9% of Kenyans have any form of social protection. Out-of-pocket medical costs push thousands into poverty annually.

Most notably private hospitals and insurers flourish while public hospitals run short of medicines, specialists and equipment.

Even the recently launched Social Health Insurance Fund (SHIF), meant to replace NHIF, is already being criticised for being unaffordable to millions in the informal sector. Kenya’s health sector increasingly resembles a two-tier system: one for those who can pay, and another for those who cannot.

This mirrors trends across the continent — from Nigeria’s overburdened public hospitals to Zambia’s strained health insurance rollout.

Taxation: When the Poor Shoulder the Heaviest Burden

Perhaps the most politically sensitive part of Oxfam’s report is taxation.

Kenya relies heavily on consumption taxes such as VAT and excise duty. These disproportionately affect low-income earners who spend almost all their money on basic necessities.

Oxfam infer that capital gains, wealth and inheritance remain lightly taxed, corporations enjoy exemptions unavailable to ordinary citizens while Kenya collects only 25 percent of its potential tax revenue.

This means the government is leaning on the poor to fund a system that benefits the elite — while simultaneously draining the budget through debt repayments that consume 68 shillings out of every 100 collected.

It is a model replicated in many African economies, including Ghana and Malawi, where austerity and debt servicing leave little room for social investment.

Women: The Unseen Backbone of a Broken System

No group is hit harder by inequality than women. Oxfam notes that: For every KES 100 earned by a man, a woman earns KES 65. Women are five times more likely to undertake unpaid care work. Only 13% of women own agricultural land.

The report also reveals that girls lose an average of two weeks of learning each year due to lack of sanitary towels.

In rural counties — Turkana, Marsabit, Wajir — the picture is even grimmer. Jobs are scarce, schools are far, and cultural expectations weigh heavily on girls. Gender is not just a demographic category; it is an economic destiny.

Oxfam’s Prescription: Bold, Political and Necessary

The report calls for radical reforms, including:

1. Stronger public services

- Make secondary education genuinely free.

- Raise the health budget to at least 15 percent of total expenditure.

- Increase education financing to 20 percent of the national budget.

2. A progressive taxation model

- Introduce inheritance and wealth taxes.

- Align capital gains tax with top income tax rates.

- Remove corporate tax loopholes and exemptions.

3. Labour market reforms

- Enforce pay equity for men and women.

- Limit the CEO-to-worker pay ratio to 20:1.

- Expand public works programs like Kazi Mtaani to absorb youth.

4. Social protection expansion

- Raise Inua Jamii benefits to match the extreme poverty line.

- Achieve at least 1 percent of GDP in social assistance spending.

Oxfam’s proposals echo successful models in Rwanda, Mauritius and Ethiopia where progressive taxation and social protection reduced inequality within a decade.

The Inequality We Create Is the Inequality We Tolerate

Larry Blackstock’s reflections about pay disparities in the NGO sector may seem like a niche workplace concern. But they speak to a larger truth running through Oxfam’s report: Kenya’s inequality is not accidental. It is engineered, maintained and normalised through policy and silence.

Whether in humanitarian offices or national budgets, the same logic applies: those closest to the work, the struggle and the suffering often benefit the least.

Oxfam’s report urges the country — and its partners — to rethink who gets left behind in the pursuit of economic growth.

The next chapter depends on whether Kenya chooses courage over complacency.