By Wahome Ngatia

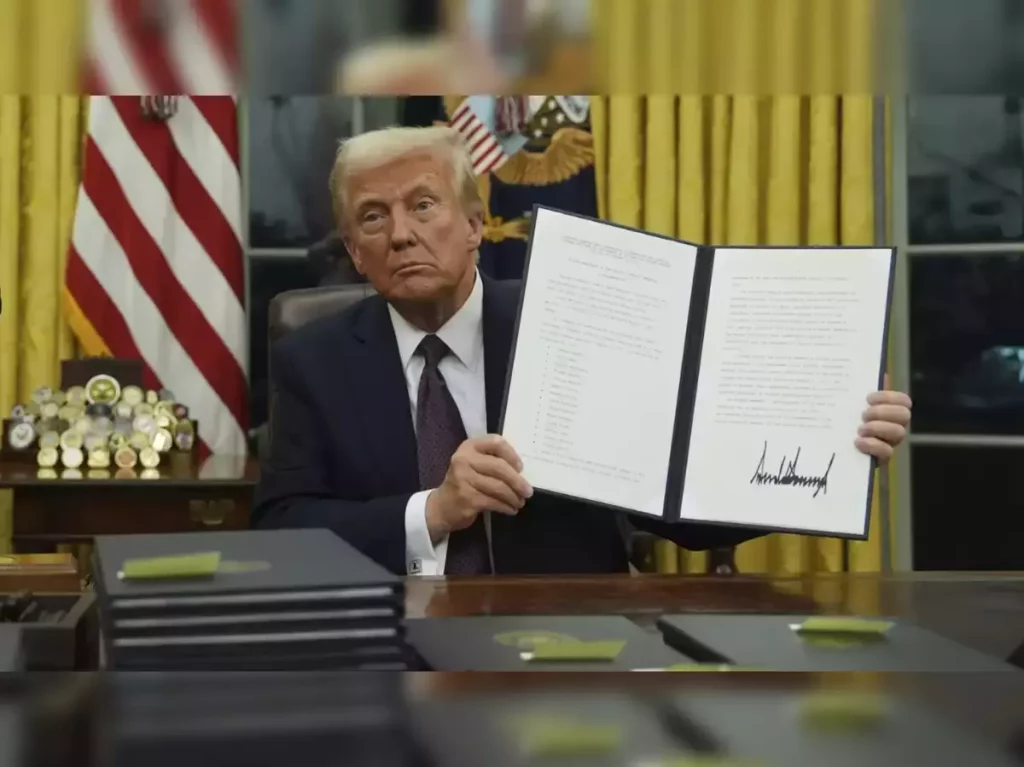

One year after former President Donald Trump signed an executive order initiating America’s withdrawal from the World Health Organization (WHO), the United States has now formally completed its exit — ending a 78-year relationship that helped shape the modern global health architecture.

The move, finalized in January 2026, marks a dramatic shift in U.S. engagement with multilateral health cooperation. At its core were deep frustrations with what the Trump administration characterized as the WHO’s mishandling of the COVID-19 pandemic, failure to adopt “urgently needed reforms,” and an alleged lack of independence from political influence by member states.

For decades, the United States was the WHO’s largest contributor. According to official figures, U.S. assessed contributions — the mandatory dues that underwrite WHOs core functions — averaged roughly $111 million annually, supplemented by about $570 million in voluntary funding for targeted programs such as polio eradication, emergency response capacities, and health system strengthening. In many years, American funding accounted for upwards of a fifth of the agency’s budget.

U.S. public health officials argued that those vast investments were not matched by commensurate influence in the organization’s leadership; notably, no American has ever served as WHO Director-General. They also faulted the agency’s early guidance during the pandemic for contributing to confusion among member states.

WHO leadership, in turn, expressed deep regret over the departure, warning that the absence of the United States weakens global preparedness for pandemics and undermines the world’s collective capacity to respond to infectious disease threats. Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus has said the decision makes the world less safe.

For an organization whose mandate is to coordinate international responses to outbreaks — from Ebola to mpox to future influenza pandemics — the loss of U.S. financial and technical engagement represents a critical inflection point. WHO provides scientific guidance, convenes global surveillance networks, and supports developing countries with diagnostics, vaccines, and health system expertise; without the United States, policymakers and disease modelers say gaps are likely to widen.

Despite the withdrawal, experts note that informal collaboration between U.S. agencies and WHO scientists is expected to continue, particularly in areas like vaccine research and genomic surveillance. But the absence of formal membership means the United States no longer sits at the table where critical decisions about global health priorities are negotiated, nor does it contribute directly to the organization’s budgeting and governance — a loss both symbolic and practical for the global health ecosystem.

For the NGO sector, the U.S. exit is more than a diplomatic footnote. It signals a recalibration of global health power dynamics at a time when equitable access to essential health tools is still fragile, and when collaboration across borders remains indispensable to confronting pandemics yet to come.