By Wahome Ngatia

When the High Court of Kenya quietly issued conservatory orders halting parts of the much‑touted Sh208 billion United States–Kenya Health Cooperation Framework, it did more than pause a government programme. It punctured a triumphant political narrative and forced a deeper, more uncomfortable question into the open: what, exactly, did Kenya give the Americans in exchange for this money?

A deal interrupted

The court’s intervention was narrow but significant. It temporarily suspended the implementation of provisions related to health and personal data sharing under the Kenya–US agreement, pending a full hearing and determination of constitutional petitions filed against it. The orders did not collapse the entire health partnership; they froze the most sensitive nerve of the deal — data — until the court satisfies itself that constitutional safeguards were respected.

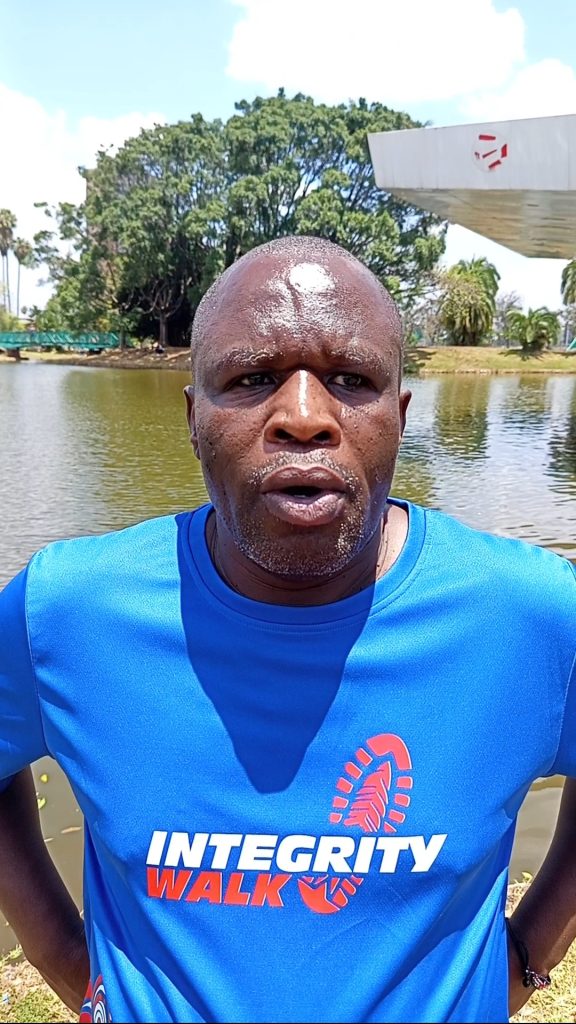

The petitions were filed by Senator Okiya Omtatah, a long‑time constitutional litigant and civil liberties crusader, alongside other public‑interest actors, including the Consumers Federation of Kenya (COFEK). Katiba Institute, a respected constitutional watchdog, joined the proceedings as an interested party.

On the other side sit some of the most powerful offices in government: the Prime Cabinet Secretary and Cabinet Secretary for Foreign Affairs, the Cabinet Secretary for Health, the Cabinet Secretary for the National Treasury, and the Attorney‑General. In other words, the entire architecture of the executive arm that negotiated, signed and sought to implement the deal.

The petitioners’ argument is straightforward and grave. They contend that the agreement was negotiated and signed without adequate public participation, without parliamentary scrutiny, and in potential violation of the Constitution, the Data Protection Act and the Treaty Making and Ratification Act. They warn that it exposes Kenyans’ sensitive health data to foreign access without clear, enforceable safeguards.

The court agreed that these were not idle fears. Conservatory orders are issued only when a court is persuaded that there is a prima facie constitutional question and that allowing the status quo to continue could cause irreversible harm. Data, once shared, cannot be “un‑shared”.

The NGO elephant in the room

But the court case is only half the story. The other half — and the one that should worry every NGO — lies in the new US foreign aid policy that sits at the heart of this deal.

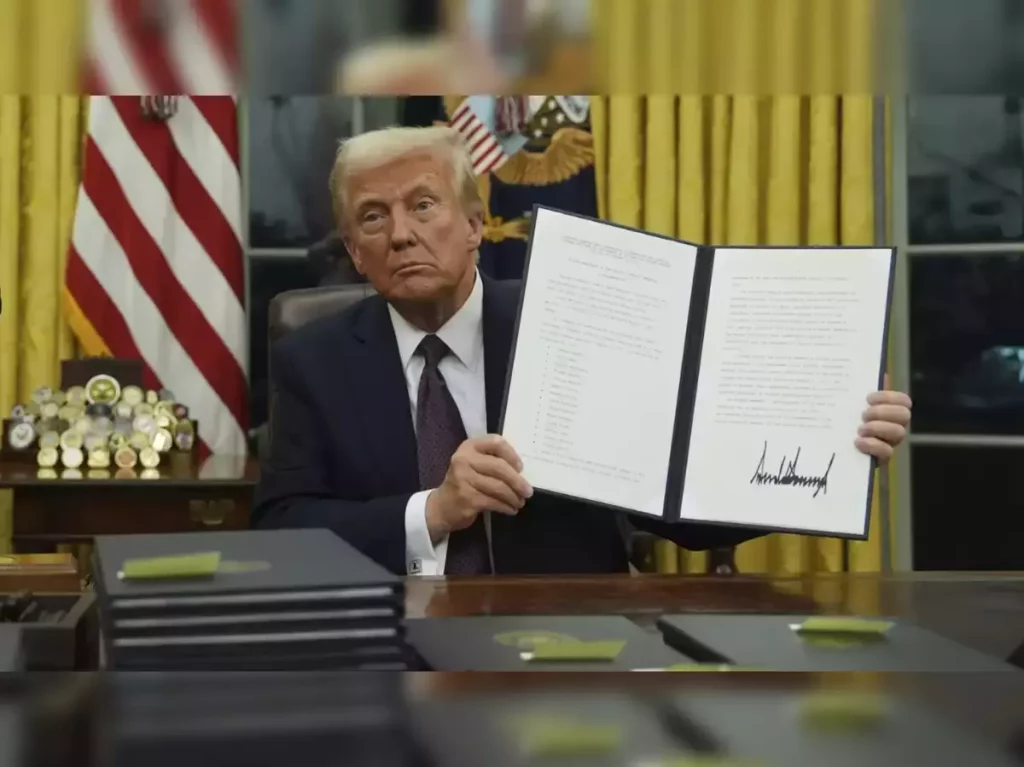

At the signing of the framework, US Secretary of State Marco Rubio was unusually blunt. The United States, he said, would no longer spend “billions of dollars funding the NGO industrial complex”. The future, according to Rubio, is government‑to‑government financing, where host states, not NGOs, are the primary custodians of donor funds.

President William Ruto echoed this position at home, telling disgruntled NGOs to “take their grievances to Washington”, insisting that Kenya did not make the decision to cut NGO funding. In his telling, the shift reflects donor fatigue with NGOs that, in his words, have sometimes failed to deliver results commensurate with the resources they receive.

For NGOs, this is not a technical policy tweak. It is an existential shock. For decades, NGOs have been the backbone of US‑funded health, governance and humanitarian programming in Kenya — from HIV/AIDS to civic education. The new model sidelines them, concentrates power and resources in the executive, and recasts NGOs as peripheral actors in a sector they once dominated.

Why the court stepped in

It is precisely this concentration of power that seems to have troubled the court. The conservatory orders serve three purposes.

First, they protect constitutional rights, especially the right to privacy. Second, they preserve the authority of Parliament, which appears to have been bypassed. Third, they pause a major policy shift with far‑reaching implications until Kenyans, through the courts, can interrogate its legality.

For government, the effect is immediate but not fatal. Implementation is slowed. Diplomatic momentum is disrupted. Officials must now justify, in open court, decisions that were previously shielded by executive discretion.

Based on Kenya’s constitutional litigation history, such cases typically take six months to a year to conclude at the High Court, sometimes longer if appeals follow. In the meantime, uncertainty reigns — particularly for NGOs already reeling from sudden funding withdrawals.

The unanswered question

This is not an argument against foreign aid or international cooperation. Nor is it a defence of NGOs as flawless actors. It is an argument for transparency, accountability and constitutionalism, especially when billions of shillings and the future of an entire sector are at stake.

The US says it wants efficiency. Kenya says it wants ownership. NGOs see exclusion. The court sees constitutional risk.

And so we return to the question that refuses to go away, the one that will haunt this deal long after the headlines fade: what did President William Ruto give the Americans in exchange for Sh208 billion — and did he have the authority to give it?

Until that question is answered in full, the conservatory orders will stand not as an obstacle to development, but as a reminder that even the biggest deals must bow to the Constitution.